Who doesn’t remember the old Western movies? They were filled with cattle drives, wagon trains, cowboys and Indians, horse thieves and cattle rustlers, vigilante justice, brave sheriffs with six-guns strapped at their sides — and strong, hard-working, kind women in long dresses and bonnets.

If you remember those movies, then you can remember the landscape too, right?

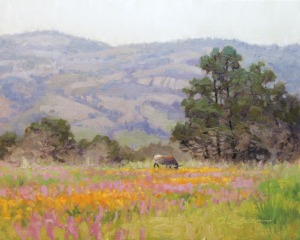

Pastures with grazing cattle, rugged hills, dry creek beds, mesquite, sagebrush, a land of big skies, a land of splendid isolation. A place where most people lived miles and miles from the nearest town, where men and women learned independence and self-reliance, where life was tough — they called it a “hardscrabble” life. But it was also a place where life was also what people had the desire, and faith, and courage, to make it, with few social conventions and traditions to get in their way.

If, in your mind’s eye, you begin to see such a place and time, then you are seeing the Texas Hill Country, just west of Austin and San Antonio, in the 1860s, and ’70s and ’80s.

It is the place and the time where the story of Texas Christadelphians begins.

Texas was a land of dreams; a land of wide horizons and wider opportunities. To men and women who passed through the deep forests of Alabama or Tennessee, and then trudged across hundreds of miles of green but monotonous Texas plains, the first sight of the Hill Country of Texas was invigorating, inviting, and even just a little beautiful, in a rugged, Texas sort of way.

The first sight of those hills still recalls the same feelings, even now, and even when encountered on a highway, in a comfortable car. You get this very view as you leave our home in Austin, and reach the

western outskirts of the city, only a few miles away. There the hills start to rise, not steeply but gradually, with long vistas broken up by little valleys. It starts to feel totally isolated, even from the 21st century. The valleys are dotted with little family cemeteries, the stones telling their stories of hardship and suffering, of babies lost to unknown diseases.

As you drive on, following the trails that the settlers of 150 years ago followed, you realize that each line of hills is followed by another, and another, and there seems no end to the hills. They climb slowly but steadily higher, and there is always another ridge.

The Texas Hill Country, also known as the Edwards Plateau, stretches out southwest and northwest from the big cities of Austin and San Antonio, until it reaches at last to the Rio Grande and Mexico, or the high plains bordering on the deserts of New Mexico, where towns have names like Plainview or Levelland. The Hill Country covers a vastness of southwest Texas greater in size than several northern or eastern states; it is about the same size as all of England.

To the first settlers, the air of the hills was drier and clearer than the air on the plains below; it felt clean and cool on the skin. The sky, in that clear air, free of practically all the pollution we take for granted these days, was a blue so brilliant that one of the early settlers called it a sapphire sky.

Beneath the trees, the Hill Country was carpeted with wildflowers in the spring, bluebonnets, buttercups and Indian paintbrush (gold and scarlet). In the fall, rather unexpectedly, the maples in the valleys turned fiery red.

Springs gushed out of the hillsides, and streams ran through the hills. Sometimes they formed dark, cold pools. After crossing hundreds of miles, the settlers from a relatively crowded and closed-in east found a landscape entirely new, and open and fresh.

The streams were full of fish, and the fields were full of deer and rabbits and huge flocks of wild turkeys. One of the first white men to come to the Hill Country wrote simply, “It is a paradise!”

To be continued.

This post is part of a series authored by brother George Booker. Click here to see all previous posts in the series.